Have you read Diary of a Worm (Cronin, 2003)? I have enjoyed it, possibly a hundred times, with my kids. It’s one of our favorites. I have even eyed it across the couch and picked it up to thumb through by myself. Yep. I find it endearing and whimsical, imagining what life could be like as a worm. I have no legs, yet my best friend is a spider with eight of them! I was cozy underground but forced to abandon my home in haste when a torrential rain threatened to drown us. Seeing the nuances of how a worm uniquely performs everyday tasks, such as holding a pencil (with a tail), sleeping (with leaves as bedsheets), and dancing the hokey pokey creates a silly connection with my everyday tasks as a human. There are other books in this series and countless other titles written from unique perspectives. (I often choose my own books based on the perspective from which they are written, too. When narrators shift each chapter, I look forward to how each character reacts internally and externally to the events in a story.)

Read-alouds such as Diary of a Worm are so valuable because they captivate our imagination while teaching us about the world. They invite us into this masterfully mixed genre that is fictional, factual, and fun. The dialogue between these characters is often comical, and the illustrations are delightfully imaginative and rich. Kids enjoy being read to with such texts, and they learn new vocabulary in the process. At the risk of igniting parental attention fatigue (can I make that into an acronym?), reading the same book over and over breeds love for the familiar characters and the setting, not to mention fluency and language structure. What’s more, the visuals facilitate comprehensible input. If you love Stephen Krashen as I do, you might go as far as to call it compelling comprehensible input, due to unique perspectives and lovable characters. (These wiggly worms know how to accessorize.)

On many occasions, I find myself in a social studies, science, or English class where the topic is intriguing. Most students are engaged, and the teacher does a phenomenal job of providing comprehensible input in the form of visuals, videos, gestures, and adapted text. This compelling, comprehensible input is particularly essential for language learners when the content is brand new for students with limited background experience with the topic.

As educators, we know that to develop language fully, the four domains must be addressed: listening, reading, speaking, and writing. Specifically, students (especially language learners) desperately need meaningful discussions, enabling them to hear, learn, and use new vocabulary and language structures that are essential to language proficiency (Wright, 2016). For teachers, the listening component might be the easiest to achieve. Many teachers are adept at reading to their audience and frequently checking for understanding. However, apprehension can set in when we consider the need for students to speak and write. “Oh, my students won’t talk. They’re good students, but I can’t get them to speak.” “They just don’t like to write.” Consider how you would fill in these blanks: Even though ______, it’s important to have students talk because ____.

Here are some possible endings to those thoughts:

Even though….

Even though some of my students are shy….they will share with a good friend.

Even though it can be challenging to bring them back together…it’s okay to give them more time to talk when it is structured and centered around the content objective.

Even when we are short on time…verbalizing vocabulary is always worth even a few moments.

Even when students struggle because it’s their second language…I can model pronunciation and voice to boost their confidence or pair them with someone who can.

Short Scripts

One way to open up a compelling space for oral development is to provide students with a short script based on characters (living or inanimate) from a book. Students are more open to speaking when playing a role other than themselves. And, obviously, the sillier the better. Below is an example of structured role-playing crafted from Diary of a Worm:

Worm: Mama, thanks for not being upset when I track mud through the house.

Mama Worm: Who’s my grubby little boy? I just love it when you’re caked in mud, sweetie.

Worm: It’s not always easy being a worm. We’re very small, and sometimes people forget that we’re even here.

Mama Worm: As I always say, the earth never forgets we’re here.

Worm: That’s true, Mama! I know that my life’s goal as a worm is to ______.

Mama Worm: You’re so wise, son! Thanks for _______.

Leaving an opportunity for students to complete sentences provides choice and comprehension. And choice breeds motivation (Escalante, 2018).

*Remember that students who are at beginner or early intermediate stages of language development might not be ready for this option.

Bilingual Example

In this page from Paletero Man (Diaz, 2021) Tío Ernesto and Frank help out a child after he has dropped his dinero and can’t pay for his paleta. This page already reads like a reader’s theater, with Tío Ernesto speaking first and the young boy responding. A class could read this in unison with half the class reading each part, or each pair of students role-playing together. Incorporating visuals such as coins and dollar bills brings the story to life as it adds dimension to the scene.

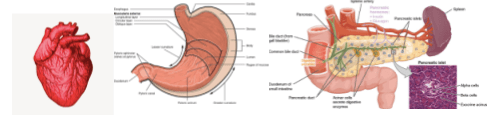

Secondary Example: Biology Role-Play

Stomach: Yummy…I love breaking down all these proteins.

Pancreas: Ease up on those sugary snacks, because I have to increase my insulin production so cells can absorb it.

Heart: Beep…Beep…I’m working harder due to my glucose levels. I need a negative feedback response to counteract the higher levels of insulin.

Stomach: Digestion is tough when we’re also trying to maintain homeostasis and equilibrium throughout the body.

Pancreas: That’s right! No organ is an island; we are all interacting with each other. Isn’t that right, heartbeater?

Heart: As chief executive officer of the circulatory system, I have to make sure we all get the proper blood flow to accomplish homeostasis!

*Special thanks to a fantastic teacher, Alejandra Cerda, for her collaboration!

The common factor in the above roleplay examples is the intentional use of content vocabulary and complete sentences. Text can be adapted, simplified, or enhanced for any language level, even as rich vocabulary remains constant. Enjoy trying unique ways to get your students talking through structured role play. Eventually, they will be writing their own!

References:

Cronin, D. (2003). Diary of a Worm. (H. Bliss, Illustrator). HarperCollins.

Diaz, L. (2021). Paletero Man. (M. Player, Illustrator, C. Tafolla, Translator). HarperCollins.

Escalante, L. (2018). Motivating ELLs: 27 Activities to Inspire & Engage Students. Seidlitz Education.

Wright, W.E. (2016). Let Them Talk! Educational Leadership, 73 (5), 24-29.