by Diane Kue

When I was young, I watched my uncle bend his neck to walk through the doorway only to then hit his head on my parents’ light fixture. I had never seen someone so tall in my life, and I asked, “Uncle Mike, how tall are you?” What wasn’t apparent to me then but is now is how annoying it was for him to be constantly asked about his height. He responded:

“I am 1 yard, 2 feet, and 20 inches.”

This wasn’t the nicest response to give a six-year-old. He knew I lacked an understanding of conversions. However, in retrospect, I have gained so much more from the engagement than his sole intent of getting me to leave him alone. I learned that answers can be unexpected and leave you with more questions. I also gained the knowledge that you can tell someone how tall they are by combining a lot of different ways to measure. I learned so much about mathematical concepts from interactions such as these with my family.

This contrasted with my school life. Growing up, my teachers, as amazing as they were, taught me procedural mathematics and focused on rote memorization and using the correct operations to get the right answers.

Think back to your school years. What was your experience in the math classroom?

Our understanding of mathematics pedagogy has evolved. Today, the focus is not on how to get the right answer but rather how to make sense of the math (Dykema, 2023). As our teaching goals change, so must how we implement instruction. Yes, immediately knowing 6 x 8 = 48 is important, but knowing when and why multiplication applies to a problem is imperative. To comprehend the why, the teacher’s role shifts from showing how to get the correct answer to prompting students to reason.

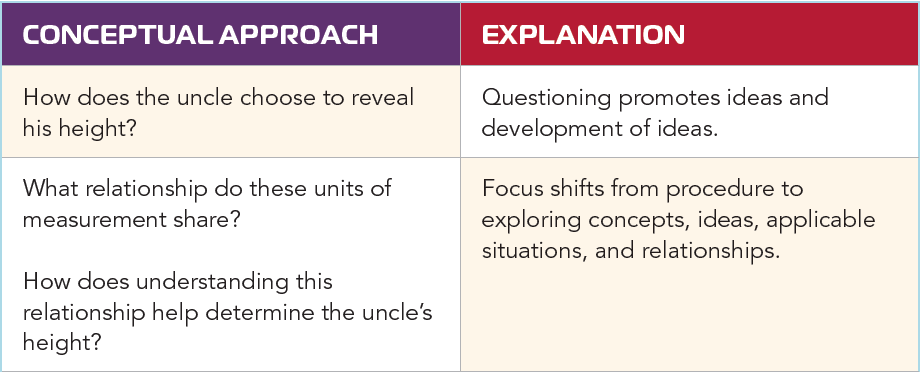

When asking a question in mathematics instruction, there are two orientations, calculational and conceptual (Thompson et al., 1994). The calculational orientation singularly centers on calculating for an answer. The conceptual orientation pivots from immediate calculating to the development of concepts, relationships, and applications. Here is an excerpt of how the two orientations manifest from my book, Solved: A Teacher’s Guide to Making Word Problems Comprehensible.

Content-based language instruction, or CBLI, is an integrated approach to acquiring language through content learning that also addresses the affective, linguistic, and cognitive needs of multilingual learners (TEA, 2023). An effective method that meets these criteria is to structure conversations in a manner so that students have low-stress opportunities to answer an open-ended question using academic discourse. This method is known as Question, Signal, Stem, Share, and Assess or QSSSA (Seidlitz & Perryman, 2011).

One reason QSSSA is such an impactful routine is because it is applicable across content. My focus is on its application in mathematics. To be explicit, the type of questions we ask in mathematics to spark discourse and conceptual application. However, this previous blog post attends to the nuances and benefits of QSSSA that I will use but not address.

Compare the student output for the two orientations in QSSSA. What do you notice?

| Calculational orientation Question | How can you calculate the uncle’s height? |

| Signal | When you have a response ready, show me the length of three inches using your fingers. |

| Calculational orientation Stem | I can calculate the uncle’s height by… |

| Share | Meet with your away partner and share your answer. |

| Assess | The person with the longest pencil will share their (or their partner’s) answer. |

| Conceptual orientation Question | What relationships do you notice between the units of measurement the uncle uses to describe his height? |

| Signal | When you have a response ready, show me the length of three inches using your fingers. |

| Conceptual orientation stem | A relationship I noticed between the units of measurement is—because… |

| Share | Meet with your away partner and share your responses. |

| Assess | The person with the longest pencil will share their (or their partner’s) response. |

With the pedagogical shift from solely solving for an answer to making sense of the math and reasoning, teachers embrace a new role. These tiny shifts in questioning promote conceptual understanding, fostering the problem-solving skills applicable beyond answering a single problem in isolation. Furthermore, when teachers prompt the use of the conceptual orientation approach in QSSSA, students advantageously learn from one another.

Want to engage in more approaches to teaching reasoning and problem-solving? Join Diane on November 13 in Dallas for an all-day workshop: Building a Foundation for Word Problem Solving.

Sources

Content-based learning instruction (CBLI) quick guide. (June, 2023). Texas Education Agency https://www.txel.org/media/bxepy3xp/cbli-quick-guide.pdf

Dykema, K. (2023). President’s message: Learning mathematics. NCTM. https://www.nctm.org/News-and-Calendar/Messages-from-the-President/Archive/Kevin-Dykema/Learning-Mathematics/

Kue, D. (2023). Solved: A teacher’s guide to making word problems comprehensible. Seidlitz Education.

Seidlitz, J. and Perryman, B. (2011). 7 Steps to a language-rich interactive classroom: Research-based strategies for engaging all students. Seidlitz Education.

Seidlitz, J. and Perryman, B. (2021). 7 Steps to a language-rich, interactive classroom (2nd ed.). Seidlitz Education.

Thompson, A. G., Philipp, R. A., Thompson, P. W., & Boyd, B. A. (1994). Calculations and conceptual orientations in teaching mathematics. In A. Coxford (Ed.), 1994 Yearbook of the NCTM (pp. 79-92). NCTM.