by Marie Heath

Just outside the Linjani tribal village, about three hours from Arusha, Tanzania, down a long stretch of dusty, rutted roads, sits Promise Village Academy.

Inside its classrooms, the air doesn’t buzz with projectors or the tapping of laptop keys. Instead, it echoes with the sound of chalk on crumbling plaster, voices reciting lessons in unison, and the soft scratching of worn pencils against well-used composition notebooks. Add to that the high-pitched screech of metal chairs dragging across concrete floors from an automatic response each time an adult entered the room as every student stood tall and greeted in chorus, “Welcome, teacher.”

In this remote region, where the Maasai children live and learn, I found a classroom unlike any I’ve seen before, primitive in resources, yet rich in potential.

When I first visited in February 2024, I came to offer something I had spent years delivering in schools across the United States: the formative training based on the 7 Steps to a Language-Rich, Interactive Classroom book. But what I didn’t realize was how much I would learn in return.

Teaching Without Electricity or Textbooks

The schools in the Ngorongoro area are basic in every sense. There’s no electricity. No running water. The only books in the classroom are worn and tattered. The walls are bare and cracked, with one black-painted wall doubling as the chalkboard. Teachers lecture while students copy notes word-for-word from the board into a single, prized possession: a composition book.

There are no student textbooks, just one for the teacher. The language of instruction is English, but the children are trilingual learners, speaking Maa at home and learning both English and Swahili at school. The pressure is intense. “Speak English” signs are hand-painted across the schoolyard, a visual reminder of the goal, but also of the weight these children carry as language learners.

The Challenge of Change

In this setting, the 7 Steps training in 2024 was both an introduction and an adaptation. Students were incredibly respectful—compliant in a way that was beautiful, but also limiting. Accustomed to direct instruction, they had learned to wait for the “right” answer rather than offer original thought. Structured conversations and student voice were foreign concepts.

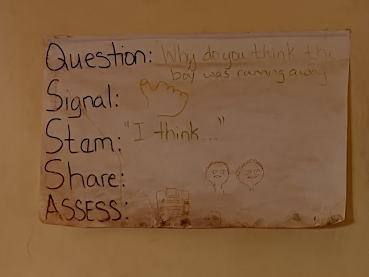

I began small: sentence stems and the QSSSA questioning strategy. I modeled conversations again and again. We wrote in the red dirt. We used dry-erase markers on old desks when paper wasn’t available. We pointed, gestured, and acted out words when visuals were lacking. Total Physical Response (TPR) became a lifeline. It was messy. It was magical.

And then, something shifted.

Returning to See the Seeds Grow

When I returned in July 2025, I was met with a beautiful surprise. Faded QSSSA posters still hung on the walls. Teachers’ 7 Steps books were dog-eared, full of handwritten notes and highlighted passages. The classrooms still lacked electricity—but they were brighter somehow.

Teachers eagerly shared how they had continued using sentence stems and encouraging student-to-student talk. This time, my focus was to go deeper—supporting teachers in designing QSSSA questions across different levels of thinking, distinguishing between those that increase engagement and those that check for understanding. We also explored how to integrate academic vocabulary into sentence stems so students could begin speaking like scientists, historians, and mathematicians.

One exciting new addition to our training was the introduction of the newly printed African Series books—stories written for and about children across the continent. The first in the series follows two Maasai children as they journey down the Nile River. I used this story as a model text to demonstrate structured reading and writing strategies.

To help bring the geography to life, I shared a large map I created of Africa showing the countries surrounding the Nile, as the translator stood beside me translating in the students’ and families’ native tongue, Maa. Teachers explored how to use the map to build background knowledge and spark interest. As students begin reading the series, they will also create their own illustrated maps—tracing the journey, learning about the people and environments along the way, and connecting literature to real-world learning.

Structured reading strategies modeled during the training included techniques such as Drop-In read, building communal word banks, using paragraph frames, and a structured approach to partner reading. In the partner reading model, students took turns reading a paragraph or page while their partner actively listened and then summarized what they heard—reinforcing both comprehension and oral language skills. These simple, low-tech strategies—paired with the culturally relevant content of the African series—equipped teachers with fresh, practical tools to deliver literacy-rich instruction, even in the most resource-limited settings.

Comparative Insights Across Continents

One of the most striking differences between teaching Maasai children and teaching students in the U.S. is access to resources. Teaching without the tools I’m accustomed to—like anchor charts, manipulatives, leveled texts, or even functioning light bulbs—forced me to stretch creatively. But it also reminded me that great teaching isn’t defined by what you have. It’s defined by how you connect.

Despite cultural and instructional differences, there are universal truths: children are naturally curious. They long to belong, and they need to be seen and heard. These truths transcend borders, languages, and learning environments.

Reflections From the Red Dirt

This experience humbled me. I thought about what it would mean to teach full-time in this environment and the learning curve I would face in delivering meaningful lessons without the resources I’ve come to rely on. I had to think like a storyteller. I leaned on music, movement, conversation, and acting, because in an oral-rich culture (without digital technology) these aren’t just strategies, they’re survival tools for learning.

I watched teachers make magic without electricity, watched students grow fluent in three languages without textbooks, and watched learning come alive in places where many would assume it couldn’t.

What I’ve seen in Tanzania will stay with me forever. Because it’s not just about what we teach—it’s about how we honor the brilliance of children, no matter where in the world they sit.

To learn more about the work at Promise Village Academy, please visit: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1o2157nvOpc95VvSqk0QMzsPRumI4Mi_a/view?usp=sharing.

Interested in becoming involved with the work at Promise Village Academy? Email Dr. Marie Moreno at: drmoreno@newcomersuccessllc.com