As a former AP teacher and AP testing coordinator, my experience has been that the role of sheltered practices in advanced classes is often underemphasized. This seems strange considering that sheltered instruction is designed to enhance language development in content-area classes, and the reading and writing demands (and for foreign languages, speaking and listening as well) of AP classes are greater than most students have ever experienced. For example, the free-response section of most AP exams is weighted at approximately 50 percent of the test, and the fast-paced timing of the multiple-choice sections means that students’ reading fluency and comprehension has to be tack-sharp for them to be successful on the exam. The notion that advanced learners do not need support in mastering advanced curriculum is simply untrue.

Sheltered instruction is made up of the practices that promote new language acquisition in the context of academic content. It was originally designed to help students acquire a new language, and academic language is very much a new language for all learners. In addition to supporting the English-language development of ELs, sheltered instruction also tends to helps students who have skills below grade level access curriculum that is at grade level.

So why wouldn’t instruction be sheltered in an advanced class? A common concern I hear is pacing: with all of the breadth of the advanced curricula, there’s simply no time for “think time” or peer-to-peer structured conversations. To this end, I propose a mind shift about the purpose of advanced classes. Instead of focusing on the quantity of material covered, let’s focus on depth of thinking. Advanced learners have advanced critical reasoning and inferencing skills, and our role as educators of advanced learners is to help them refine those skills.

For example, consider the transcarboxylic acid cycle (TCA cycle, for short) from the AP Biology curriculum. This is a process cells use to create usable forms of chemical energy. There is a multitude of names and structures of intermediate molecules involved in the TCA cycle, and the TCA cycle represents just a small fraction of energy processes that occur in cells and organisms. It is understandable, therefore, why an AP Biology teacher might feel compelled to directly lecture about the TCA cycle in addition to other energy processes and have his/her students study the molecules’ names and structures for homework.

To provide a more engaging and thought-provoking lesson, the teacher could take a more sheltered approach. Students could be shown a diagram of the TCA cycle with labelled input reactants and output products and a diagram of those reactants and products in other processes. Using these visuals as anchors of support, students could then have structured conversations about how the TCA cycle enhances energy production in the presence of oxygen and how the TCA cycle relates to oxygen and carbon cycling within ecosystems. For example, each student in a group of three or four could share their thoughts with each other one at a time, using the sentence stem “One way the TCA cycle relates to oxygen cycling is…” Students could discuss connections to the evolution unit within their groups and finish the lesson by writing about how oxygen-rich environments allowed for the evolution of more complex species.

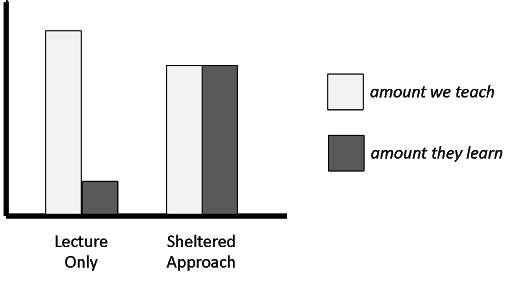

How do these two approaches compare? While the direct-teach approach certainly allows for more material to be covered in a class period, it is also firmly centered around the “remember” level of Bloom’s taxonomy. The sheltered approach, by contrast, focuses on analyzing and applying while reinforcing facts and basic ideas. The sheltered approach also gives students support in thinking about the new material through multiple visuals and the sharing of diverse schemata to come to a common understanding in structured conversations. This support, combined with the opportunity to write about connections between the TCA cycle and other units of study, is more likely to result in long-term learning of the material. I sometimes think of sheltered instruction in terms of efficiency. Sure, direct-teach will result in more material “covered” in less time. But if students are ultimately retaining only a fraction of what they’re being taught, what is the point?

The sheltered approach also differs from the direct-teach approach in that it makes deep thinking opportunities available to all students. It’s a common phenomenon for the same three to five hands to go up every time a question is asked, and advanced classes are no exception. When this happens, however, much of the rest of the class feels disempowered to think deeply, since the question is already going to be answered before they have the chance to really think about it. A sheltered approach — with total participation as a cornerstone and in which students are able to share their thoughts in small groups — ensures that all students engage in rigorous thinking.

Recommendations for Sheltering Advanced Classes

- Ask open-ended questions based on a primary text, dataset, or model. Advanced learners need to practice and refine critical reasoning and inferencing skills, and having them draw information from complex visuals is a great way to practice those skills. Importantly, learning happens through language, so be sure to have them discuss those questions in partners or groups. I recommend multiple questions related to the visual(s) for them to discuss over several minutes.

- Make critical writing a central component of every lesson. Challenge students to improve their writing by showing them examples and non-examples and giving them opportunities to share their written products with each other. One way to do this is to have a one-to two-paragraph writing prompt as the assignment for the final ten minutes of class. Give them five to seven minutes to write, then in the final three to five minutes, have them share with each other and/or the class. An additional layer to help them improve their writing is to give them the same (or similar) writing prompt as a warm-up activity for the following day. This will also help them make connections between lessons.

- Choose two to four vocabulary words to emphasize each lesson. Introduce the words at the beginning of the lesson with a visual, and have students practice pronunciation of each word. (I don’t know about you, but I certainly wouldn’t feel confident saying transcarboxylic acid cycle in front of the class without some practice pronouncing it first!) Encouraging students to use these key words in their structured conversations and in their writing will help them firmly lock each word into their lexicons.

Ultimately, a shift to more sheltered practices will result in students reading, writing, speaking, and thinking like experts of their field. With a solid acquisition of academic language, the sky is the limit for all learners!

Dr. Fleenor is the author, with Tina Beene, of the new book and training, Teaching Science to English Learners. Join us in Dallas on October 3!